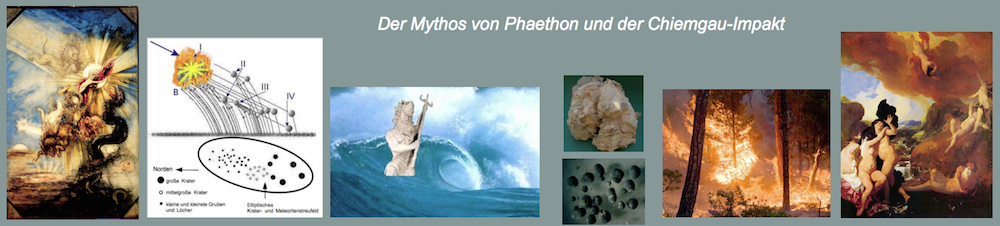

A prehistoric meteorite impact in Southeast Bavaria (Germany): tracing its cultural implications

by

Barbara RAPPENGLUECK 1, Kord ERNSTSON 2, Ioannis LIRITZIS 3 , Werner MAYER 1, Andreas NEUMAIR 1, Michael RAPPENGLUECK 1 and Dirk SUDHAUS 4

1Institute for Interdisciplinary Studies, Bahnhofstrasse 1, 82205 Gilching, Germany. 2Julius‐Maximilians-Universität Würzburg, Am Judengarten 23, 97204 Höchberg, Germany. 3University of the Aegean, Dept. of Mediterranean Studies, Lab of Archaeometry,Rhodes, Greece

4Albert‐Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg, Institut für Physische Geographie, 79085 Freiburg, Germany.

34th International Geological Congress, August 5-10, 2012 – Brisbane, Australia

Here we report on a prehistoric meteorite impact in the very Southeast of Germany. In reference to the name of the affected region, the Chiemgau, the event is called the “Chiemgau impact”.

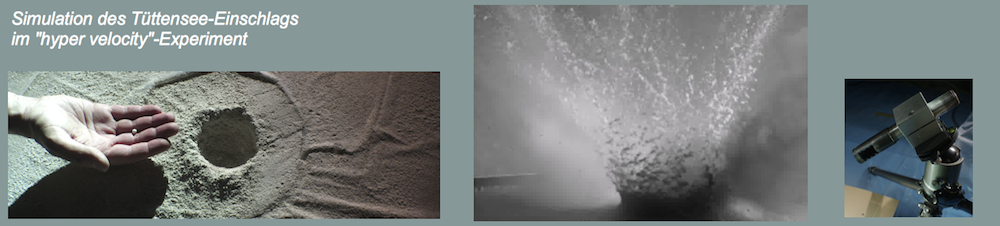

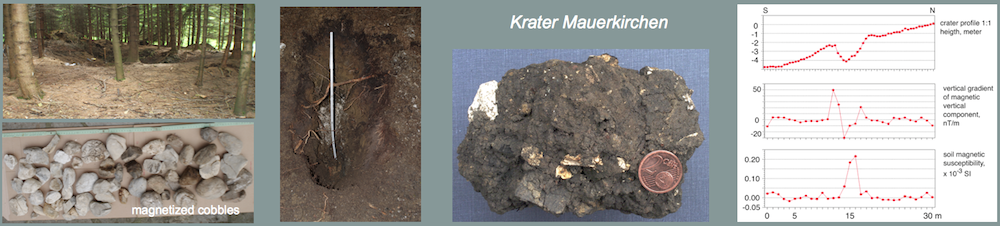

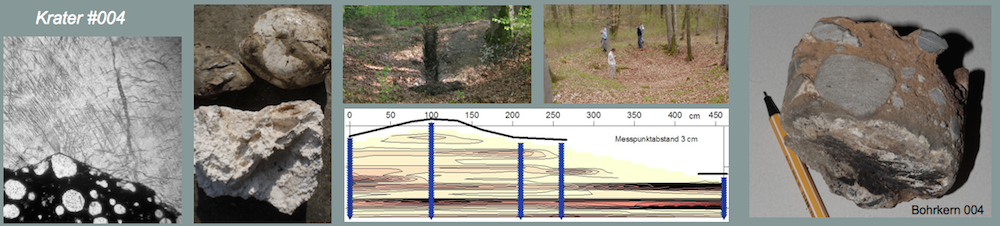

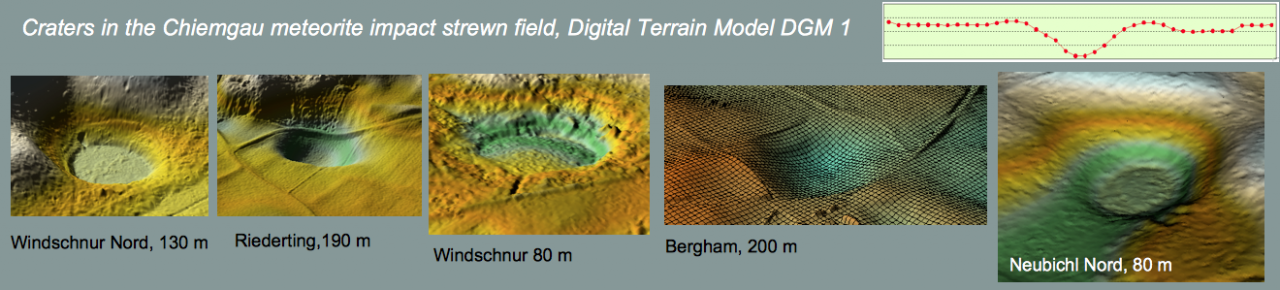

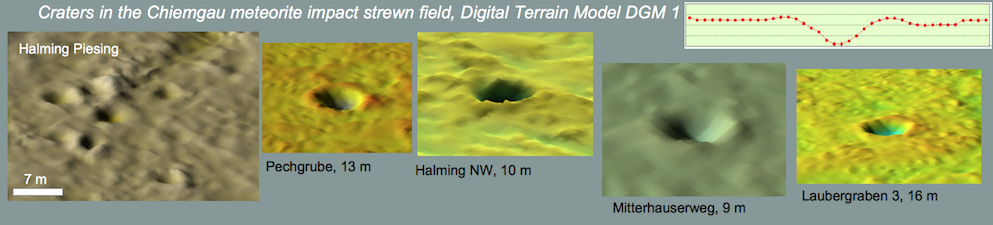

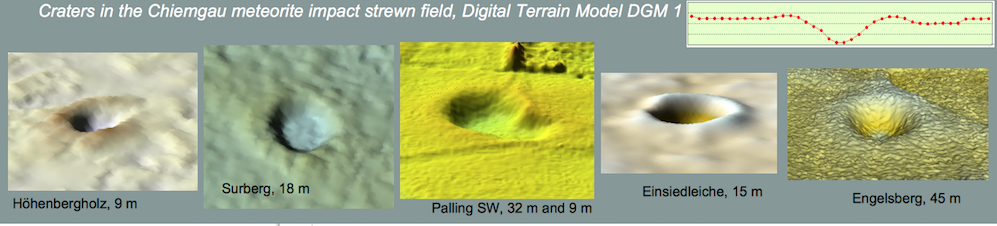

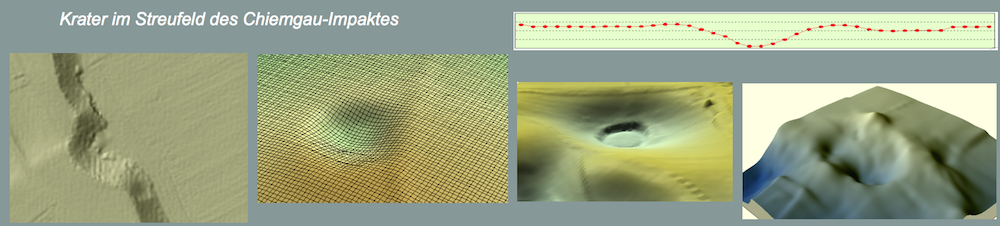

The crater strewn field of the Chiemgau impact spans more than 80 mostly rimmed craters in a elliptically shaped area with axes of ca. 60 km and 30 km. The diameters of the craters range from a few meters to a few hundred meters. The biggest crater, that of Tüttensee, which nowadays is filled by a lake, exhibits an 8 m-height rim wall, a rim-to-rim diameter of about 600 m, a depth of roughly 30 m and an extensive ejecta blanket.

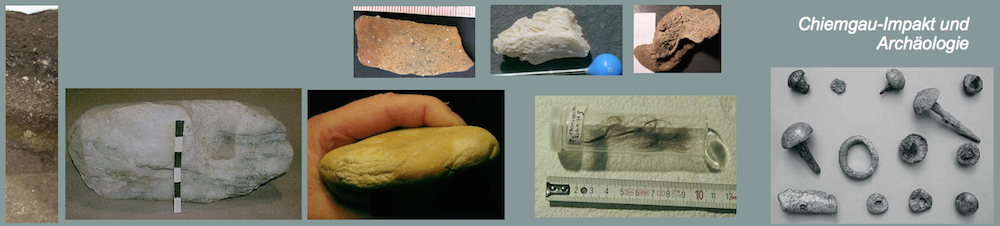

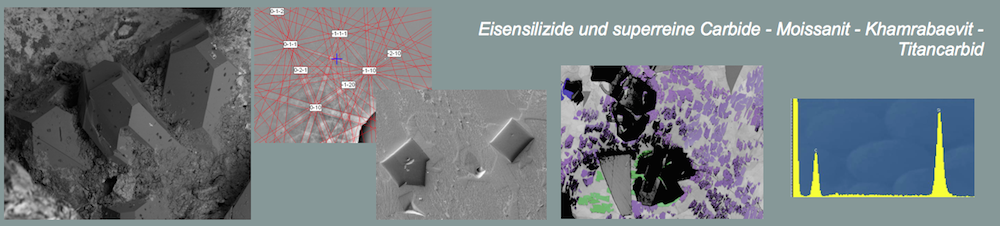

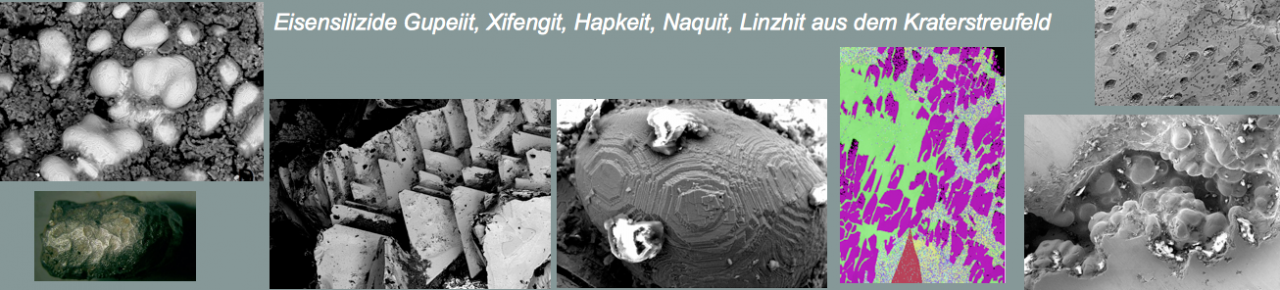

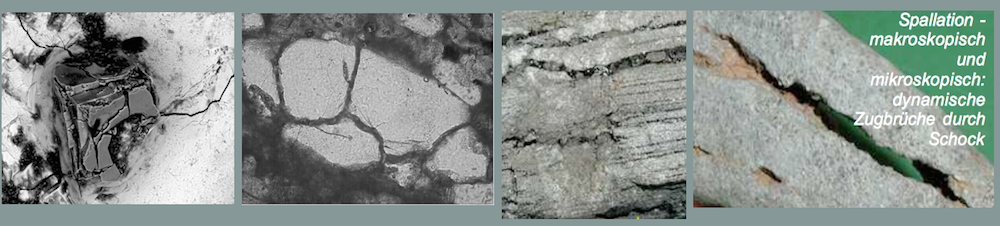

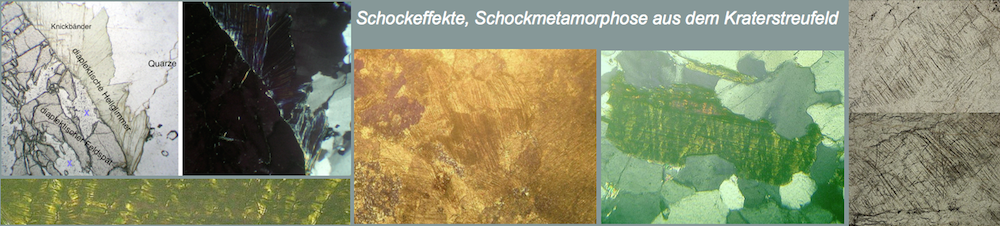

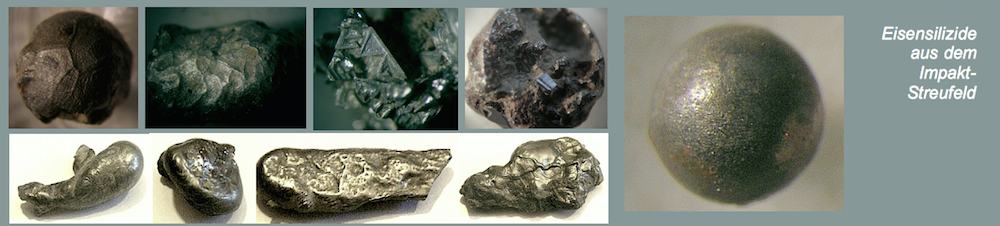

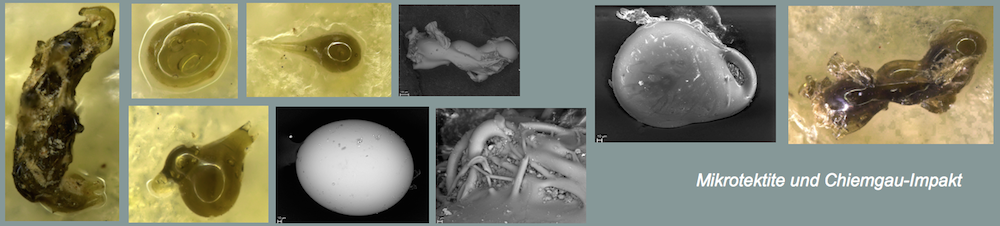

Meteorite impact research has some criteria to prove an impact, each of them being valid on its own to do so. One of these criteria is the evidence of shock metamorphism of quartz in the form of so-called Planar Deformation Features. They require a shock pressure of more than 10 GPa and can in nature only be obtained by a meteorite impact. Such shock effects have been attested in cobbles from the big Tüttensee crater as well as from some much smaller craters in the strewn field. Another criterion is the find of material of the meteorite. Samples of iron silicides gupeiite and xifengite, which have been found in the area, are very similar to the ureilite type of meteorites and very probably represent parts of the meteorite.

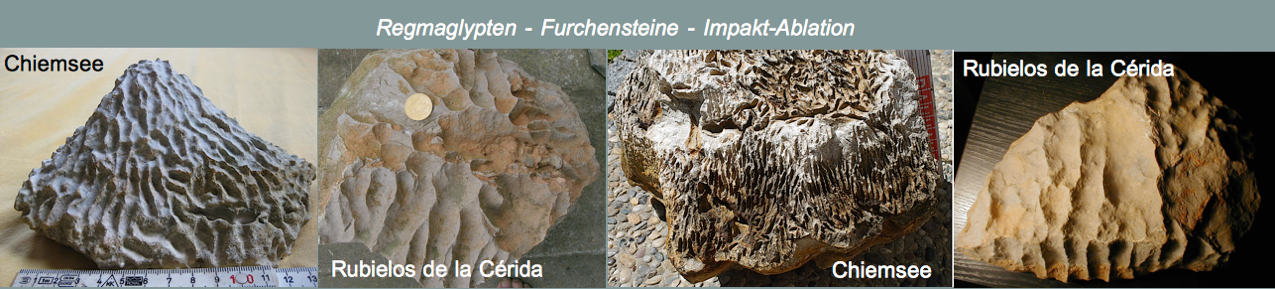

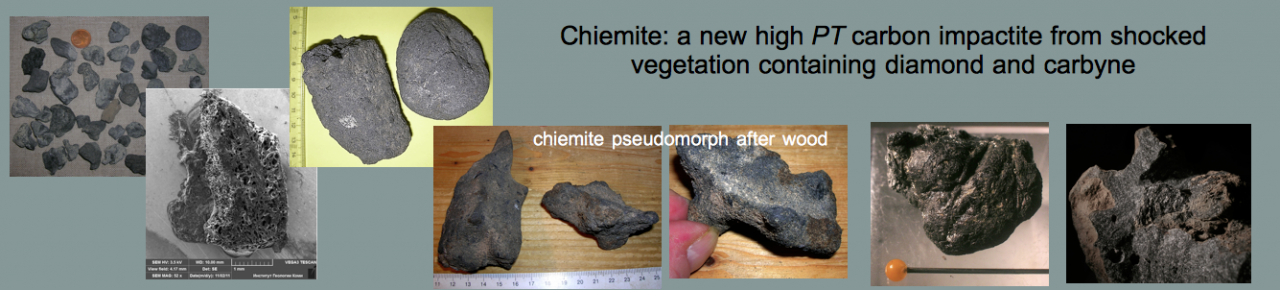

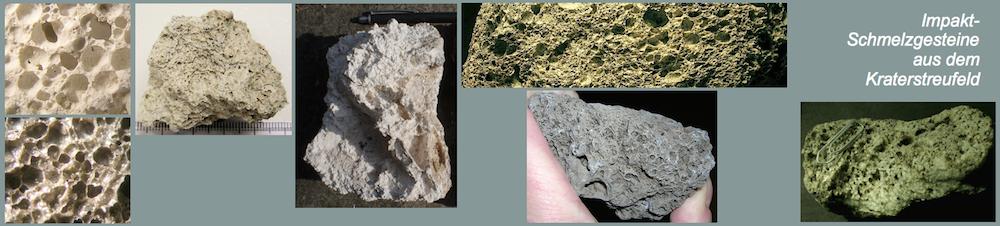

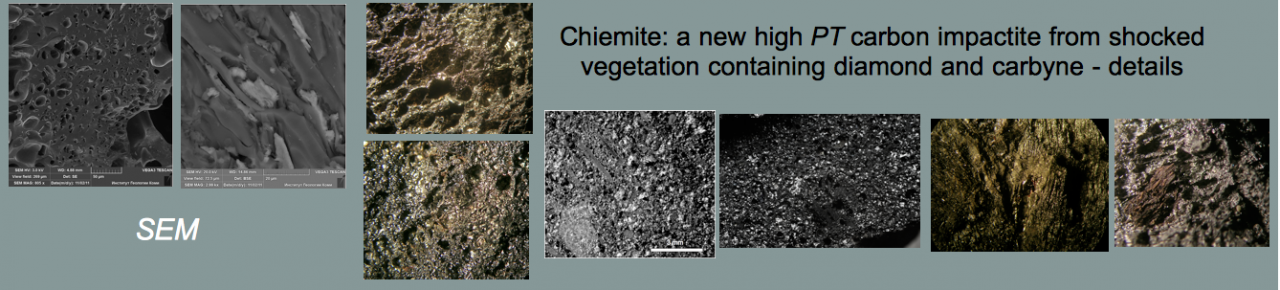

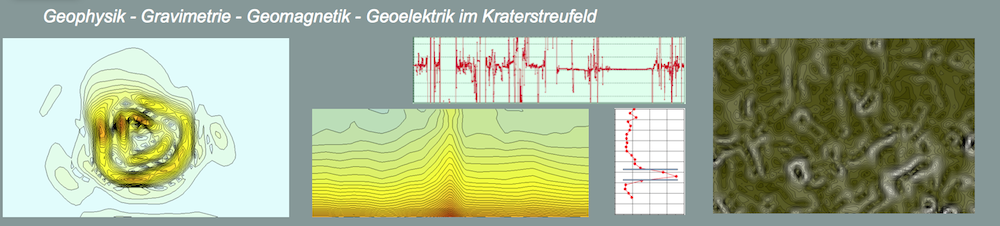

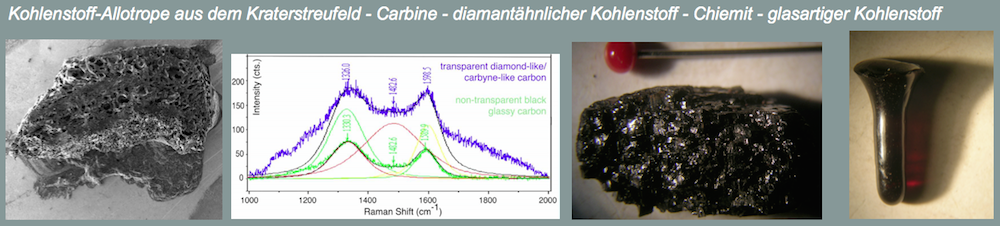

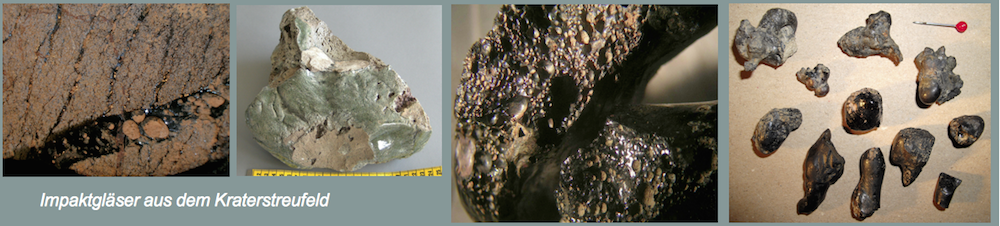

Furthermore, the Chiemgau impact exhibits a big variety of secondary phenomena. They are not diagnostic for a meteorite impact, but important to be mentioned with respect to their potential effects on humans and their cultural response. Carbon spherules were found embedded in the fusion crust of cobbles from a crater as well as in soils widespread over Europe. This occurrence suggests an extended fallout phenomenon. Some rocks show various forms of melting and vitrification, other ones are corroded down to skeletal formation. The latter is not only attributed to a decarbonisation process but probably also to dissolution by nitric acid precipitation from the impact explosion cloud. A gravity survey of the Tüttensee crater and its environs revealed an anomaly of positive gravity. It can be explained by soil liquefaction and densification generated by the high-energy shock pressure of the impact. Cobbles and sand embedded in peat bogs close to the glacially formed Lake Chiemsee, which is with 80 km2 the biggest lake of the region, point to tsunami-like waves of several meters height, caused by one or several impacts into the lake. Sonar soundings in Lake Chiemsee which revealed the structure of a double-crater support this evidence.

The Chiemgau impact can be dated to ca. 2200-500 BC, i. e. the Bronze Age/Iron Age, most probably even to 1300-500 BC, i.e. the Late Bronze Age Urnfield culture or the Iron Age Hallstatt culture. This dating has been obtained by combining radiocarbon and OSL dating with dating based on archaeological artifacts. During an archaeological excavation located a few hundred meters apart from the shoreline of Lake Chiemsee, the unique situation was encountered of the catastrophic impact layer outcropping in the archaeological stratigraphy. In this layer as well as in the ejecta layer of the Tüttensee crater potsherds were found, dating most probably to the Late Bronze Age Urnfield culture. But the discovery of an Iron Age Hallstatt potsherd and an iron lump in the catastrophic impact layer also keeps the Hallstatt period in consideration.

The dimensions of the Chiemgau impact suggest some environmental and cultural effects within the time under consideration, i. e. 2200-500 BC. Pollen diagrams of the region are not analysed and dated exactly enough to catch a punctual event and its potential effects. The archaeological database reveals several periods of reduced or missing settlement evidence. Lakeside pile dwelling settlements of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age are missing at Lake Chiemsee, while they are common at other large lakes in the Alpine Foreland. Furthermore, the Chiemgau region shows a decline in settlements in the late Urnfield culture, shortly after 1000 BC. Later on, during the Hallstatt period, the area explicitly lacked the so-called Herrenhöfe (“farmsteads”), which are otherwise characteristic settlement structures in southern Bavaria.

So far it is impossible to attribute one of these settlement declines to the Chiemgau impact. We are confronted by the fact that a number of aspects have to be pondered in tracing the maybe cultural effects of a meteorite impact of this size, and that there exist hardly any relevant data from other Holocene meteorite impacts for comparison. Till now it is very hard to estimate the extension of the effects of the impact and of its secondary phenomena and to balance it with the available archaeological data. In addition, in case of the Chiemgau impact it must be borne in mind that it does not fit into the “one object – one impact – one crater” category and the related models that sketchily appraise the environmental and cultural effects in dependency on the size and the energy of the meteorite.

Hence we face a somewhat absurd situation: In comparison to other Holocene impacts the Chiemgau impact provides extraordinary data by the extension of its crater field, the size of the biggest crater, the variety of secondary effects, the direct embedding of the impact layer in an archaeological stratigraphy, and the comparably good dating. Nevertheless we are not yet able to grasp its environmental and cultural effects. Any decline of – let us say – 100 years may easily slip through the net of any dating method, and any interpretation of available data is overstrained by missing knowledge how to outbalance the different factors in case of a meteorite impact of this size.

Nevertheless we are confident to have found one specific cultural response to the Chiemgau impact. The Greco-Roman myth of Phaethon, the son of Helios, is supposed to reflect details of the Chiemgau impact event. Phaethon performed a disastrous ride with his father’s sun chariot, was struck by Zeus’ thunderbolt, and tumbled to Earth, together with the fragmented chariot. The descriptions of Phaethon’s course along the sky and the details of his fall, transmitted by ancient classical authors, perfectly depict the approach of a meteoroid and the phenomena which occur during its passage through the atmosphere. There is e.g. the staggering fall head first, or the combination of Phaethon’s reddish burning hair with his pitch-dark veil. Beyond that many details of the myth correspond closely with geological facts encountered in the field of the Chiemgau impact. Zeus’ thunderbolt and the fragmentation of the sun-chariot correspond to the explosion of the meteoroid in the atmosphere, to its cascading fragmentation and to the abundant number of craters. The description of Phaethon as a black globe or as being enwrapped by fiery ash, and the world to be covered by Phaethon’s ash reminds of the extended fallout-phenomenon of carbon spherules. Charcoal, which is abundantly found in the impact layer, may represent the relicts of the wildfires that burnt up the country after Phaethon’s fall. Some ancient authors mention that Phaethon fell into a lake. Here we point to the evidence of a double crater in the bottom of Lake Chiemsee. The god Neptun is reported to have three times risen his head and arms from the water. This seems to describe very well a tsunami induced by one or more fragments plunging into Lake Chiemsee. Furthermore, the myth tells us that Tellus, the goddess of the earth, rose her face and sunk with a big quake, shaking all, and then sat somewhat deeper than before. A gravity survey of the Tüttensee crater and its environs suggests a liquefaction and densification of the highly porous target rocks, which was caused by the high shock pressure of the impact. Soil liquefaction and ground subsidence are well-known in the context of strong earthquakes. The description of Tellus sitting down with a big tremor and being seated lower than before seems to provide a perfect description of such a process.

Numerous indications are provided by classical authors for the fall of Phaethon being situated in Northern or Western Europe. Some of them explicitly stated that the land of the Celts had been the scene of action. This coincides with the fact that the Chiemgau impact is situated in the core region of the former Celtic culture. The oldest possible age of the myth is estimated by the age of the motive of the sun-chariot and from archaeological evidence of light chariots drawn by horses in general. That way ca. 2000 BC might provide the terminus post quem for the tradition of Phaethon’s disastrous ride. This date corresponds quite well with 2200 BC as the terminus post quem for the Chiemgau impact.

How could the details of the event be transmitted and encoded in a myth? The described details require the presence of eyewitnesses close to the area of the impact. From the Tunguska cosmic event of 1908 a number of detailed reports exist, provided by persons concerned, who experienced the event at a distance of 10-60 km from the epicentre. The topography of the Chiemgau area with its hilly landscape and many lakes and rivers may have incalculably influenced the very local effects of the impact and may have provided insular shelters, e.g. in the lee of a hill. Also the proximity of this region to the Alps has to be considered. The first peaks, rising up to 1500-1700 m and about 10 km away from the biggest crater, provide a perfect vantage point. From there any observer who managed to find shelter could have observed the scene in detail.

But what might have prompted Mediterranean people to construct the Phaethon myth based upon an event that took place in a remote area? It is important to realize the dimensions of the Chiemgau impact event. The reconstructed trajectory must have made people of at least all Northern Eurasia eye-witnesses of the fiery entrance of the celestial object. The explosion of the body in the atmosphere, supposed to have taken place at an altitude of ca. 70 km, could have been visible within a circumference of at least a 500-600 km radius. The sound of the explosions could probably been heard from a distance of 1000 km or even more. The ground may have been shaking several hundred kilometres away. Fragments of the exploding body may have caused the phenomenon of “stone rain” even in parts of southern Europe while the fallout of carbon micro-spherules would have affected wide parts of Europe. Concerning the Mediterranean world, different phenomena must have been noticeable in Northern Italy and some of the effects probably even in more distant parts of Southern Europe. In addition, information of this apocalyptic event would have rapidly spread and reached the Mediterranean world by the established routes of trade and other contacts. The retelling of these experiences and associated information must have called out for an explanation: it was an event that was clearly in sharp contrast to the regular order of the cosmos. The myth of Phaethon would have provided an appropriate answer, a narration that ended up describing the anomalous event, not as a physical reality, but rather as a mythical rendition of what was shocking experience in the context of the traditional view of the cosmos.

The research in the Chiemgau impact illustrates the problems to verify cultural effects of an impact event even of such a size and character, and despite of a comparable good database. But on the other hand the results already available show that among the Holocene impacts the Chiemgau impact provides an extraordinary and very promising case-study for the question of Holocene impacts and their cultural implications.